|

|

| |

| Causative Agent |

-

A

tick-borne, potentially

zoonotic, disease primarily of

rodents and

lagomorphs. Caused by the

bacteria, Francisella tularensis.

-

Two different sub-species of

F. tularensis:

-

one holarctic (F. t.

palaearctica);

-

one restricted to North

America (F. t. tularensis).

|

| Images |

|

Click on

images to enlarge. |

|

|

|

Small white dots of necrosis

on the liver of this beaver are typical of tularemia. |

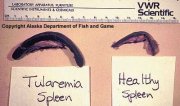

Enlargement of the spleen is

typically observed in animals with tularemia. |

|

| Distribution |

|

Geographic: |

-

In North America:

-

F. t. tularensis

occurs in terrestrial

habitats;

-

F. t. palaearctica

occurs most often in aquatic habitats

(wetlands and boreal areas).

-

F. t. tularensis

does not seem to occur in

Canada and may be limited to the lower 48 contiguous United

States.

-

F. t. palaearctica

infection primarily occurs

in Canada.

|

|

Seasonality: |

-

Ticks

are

only present on hares from May to September (based on Alaska

data); as a result, the disease essentially disappears from

October through April.

-

Human cases may also occur throughout the fall and winter

following exposure to

lagomorphs during hunting season.

|

|

| Hosts, Transmission and Life

Cycle |

| Hosts: |

-

F. t. tularensis: rodents and

lagomorphs.

-

F. t. palaearctica:

aquatic rodents.

-

In North America, tularemia occurs most commonly in cottontail rabbits (Sylvilagus

spp.), muskrats (Ondatra

zibethicus), ground squirrels (Sciuridae), and beavers (Castor

canadensis).

-

It is thought that tularemia is often fatal in the above species, but not

so for the snowshoe hare (Lepus

americanus).

|

|

Transmission: |

-

F. t. tularensis:

transmission occurs among hosts primarily through

ticks, but

also by

mites,

mosquitoes, fleas,

lice and

biting flies (Tabanidae).

-

F. t. palaearctica:

transmission occurs directly through water, which may remain

infectious for weeks to months following contamination.

-

For

both sub-species, transmission may also occur through contact

with feces, urine or body parts of infected animals.

|

|

Life Cycle: |

-

Although often fatal, the

bacterium can infect both

lagomorphs and rodent hosts without

apparent ill-effects. These hosts can then remain infected

for extended periods, serving as

reservoirs of infection for other animals and

biting arthropods.

-

Ticks

act

not only as

vectors of transmission, but also

as

reservoirs of the

bacterium, which can live in certain

tick species for months.

-

F. t. palaearctica

may

also be transferred among voles (Microtus spp.)

through cannibalism of infected individuals.

-

The

associations between mammal and

arthropods differ from location to

location.

|

|

| Signs and Symptoms |

|

Animals: |

-

In the most sensitive

species,

clinical signs are not often observed due to the short duration of

infection before death occurs. These animals are usually in good

body condition at death.

-

In less sensitive species, during the latter stages of

the disease, animals may become lethargic or depressed and have

elevated body temperature.

-

Tularemia is most often recognized during examination

at a

diagnostic laboratory.

-

Tiny, pale spots on the liver, spleen or lung are

typical

lesions of

tularemia.

-

Spleen or liver may become enlarged.

-

As

in humans, an

ulcer may

form where the

bacteria have entered the body.

-

Thin, whitish strands of material may be present in the

abdominal cavity.

-

The

lesions

described above are not unique to tularemia: see also

plague.

|

|

Humans: |

-

Initially, symptoms

are: generalized fever-like illness (e.g., fever with chills,

headache, vomiting) beginning 1-10 days after infection.

-

Confirmation of the

disease is usually accomplished using blood tests.

-

The course of the

disease depends on the route of infection:

-

arthropod

bite: an

ulcer

forms at the bite wound followed by enlargement of the

lymph nodes draining the area of the bite wound;

-

inhalation: inhalation of infected material results in

pneumonia;

-

ingestion: infected water or meat that is ingested

leads to

inflammation of the posterior portion of the oral cavity and

intestines.

-

Disease resulting from F. t. tularensis is more

serious than that caused by F. t. palaearctica.

-

Death occurs in 40-60% of untreated cases

where

pneumonia or

inflammation of the inner surface of the intestines

occurs, and 7% of all

forms of untreated infection with F. t. tularensis. In

contrast, fatalities occur in 1% of untreated infections with F.

t. palaearctica.

-

Human to human transmission is rare.

-

F. t. palaearctica

is

common in trappers.

|

| Meat Edible? |

-

Normal cooking

temperatures destroy

bacteria in

the meat; it is, therefore, safe to eat when thoroughly cooked.

-

Human exposure typically results from preparing carcasses.

|

| Human Health Concerns and

Risk Reduction |

-

Human infection in

North America prior to 1950 has been closely associated with

exposure to cottontail rabbits infected with the F. t. tularensis

strain.

-

After 1950, the major

risk factor to humans has switched to muskrats infected with the

F. t. palaearctica strain.

-

Taking certain

precautions can reduce the chance of exposure to the tularemia

bacteria,

such as: basic hygiene, use of insect repellents and

protective clothing to avoid

arthropod bites, inspection and removal of

ticks,

use of gloves when handling and dissecting wild animals,

particularly rodents and

lagomorphs.

-

Vaccination against tularemia may be warranted in

high-risk areas.

-

Dogs and cats can die from tularemia. Since infected

animals are easier to catch, pets may become infected after eating

the internal organs of the diseased animal. Keeping pets from

roaming free should help to reduce the spread of tularemia.

-

Tularemia is readily treated with antibiotics if

treatment is started early in the course of the disease. Thus,

symptoms of general malaise and fever should not be ignored and

medical attention sought. Medical personnel should be advised that

you may have been exposed to wildlife and so may be at risk with

respect to various wildlife diseases including tularemia.

|

| Samples for Diagnosis |

-

Submission of entire

carcass or just the spleen or liver.

|

| Similar Diseases |

-

Lesions in animals

infected with

plague,

yersiniosis and other

bacterial infections may be similar to that of tularemia.

|

| Further Reading |

|

|

|

|