Honouring Strength: Overcoming Addiction Identities

Adapted from Thesis, by Jeff Talbot B.Sc., BSW,

MSW Cand., RSW

I bought into this belief that everything I was, was because

of alcohol. So I was basing who I believed I was on my supposed

greatest weakness. Now that’s tough. How do you get ahead?

(Judy)

My thesis explores how some people manage their relationship

with / without alcohol in ways that do not seem to harmonize with

status quo discussions of alcohol abuse and recovery. My question

was: How do the experiences and needs of those overcoming addiction

independently of 12-step / disease-model culture impact social

work practice? This qualitative study explores experiences of

seven "outsider" participants. Two quit drinking completely without

the help of addiction therapy or self-help groups; the remaining

five participants reclaimed a manageable relationship with alcohol

after years of dedication to 12-step programs. The participants’

experiences are explored using a social constructionist cultural

model. Issues regarding the political context of addiction counselling

are explored, and implications including assessment and resource

development for social work practitioners are discussed.

After 20 years as a social worker / alcohol and drug counsellor

in northern British Columbia, my practice has been greatly impacted,

strangely enough, by political rhetoric. After earning a degree

in psychology, I found that strategies I learned were not acceptable

to the support agencies in the town where I started my career,

unless they were within the theoretical boundaries of the disease

model and the 12-step approach to treatment for "alcoholics" (a

self-proclaimed title). I understood the practical reasons for

this policy; essentially, before alcohol and drug counsellors

were available, the local community depended on Alcoholics Anonymous

as the only support for people with alcohol problems. Later, as

I earned my BSW and moved to a somewhat larger northern community,

I found there was more room for a variety of approaches in a multi-staff

alcohol and drug counselling office. I found that, as a result,

I had a front-row seat to the political turf wars between multiple

recovery cultures. Polemic disputes occur on several levels. One

concern is over the ethical dilemma of client self-determination

versus a prescriptive disease model that assumes that "insanity"

and "denial" (terms often used in 12-step literature) preclude

the client’s capacity to make healthy choices. Another level

relates to policies and practice of harm reduction versus zero-tolerance

and tough-love approaches. The conflict also highlights disputes

about the context of expert knowledge (those with personal experience

versus those without). The fundamental issue is the debate over

alcohol addiction as individual experiences of one truth, one

journey, and one solution informed by pathologizing practice,

versus a perspective of addiction as individual experiences with

multiple knowledges, journeys, and many uncharted territories

where outsiders find themselves (Korzybski said that "the map

is not the territory" (Truan, 1993). Consequently, the uncharted

is beyond the conception of the rhetoric commonly used to understand

the experience of addiction).

People have been coping with the negative consequences of

drinking alcohol since the beginning of civilization. However,

how these causes and consequences associated with drinking problems

are defined varies according to culture. For example, modern western

perspectives of alcohol addiction management are heavily influenced

by medical positivist research (Peele, 1989). In contrast to positivist

traditions, cultural studies theorists (Alasuutari, 1992; Bannerman,

2000; Denzin, 1993; Gusfield, 1996; Pinderhughes, 1989) have played

an instrumental role in informing my research of alcohol problems

and recovery. As Pinderhughes (1989) observes, "Culture determines

how we see a problem and how we express it¼

" and culture can "determine what specific symptoms people experience,

whom they seek out for help, and what they regard as helpful"

(p.13). Key concepts that are useful from cultural studies include

the valuing of discipline-jumping and genre-jumping; bricolage;

polyvocality; and incompletion or non-closure of knowledge. These

concepts embrace some postmodern assumptions: that reality is

subjective in relation to our experience, and that experience

is informed by more than one framework. Consequently, knowledge

itself is as relative as our self-awareness in relation to people

we observe (Furman & Ahola, 1992; O’Hanlon, 1993; White,

1993).

This study was developed based on a relatively regular phenomenon,

which has fascinated me throughout my career as an addictions

counsellor. I have witnessed individuals who were able to establish

a more meaningful identity in relationship with alcohol after

many years as an "alcoholic" or "alcohol-dependent" person. This

has occurred in spite of a general belief among addiction treatment

professionals that those with serious substance abuse problems

warrant a "substance-dependent for life" label. Consequently,

these persons achieved their success by methods outside the boundaries

of traditional disease rhetoric and intervention.

The controversy created by outsider experiences reflects,

from a cultural studies perspective, the influences of more dominant

cultures and how these ideas seep into the community in which

this study was conducted. Dominant ideas are sold through a market-driven

deluge of television shows, magazines, music, and newspapers.

This subtle or overt propaganda is disseminated through many modes

and role models. For example, a key character in the award- winning,

long-running ABC network television series NYPD Blue(episode

65, "Closing Time," broadcast on May 14, 1996, written by David

Mills and directed by David Rosenbloom), detective Sipowicz (played

by Dennis Franz), suffers loss of control over his drinking. The

character’s capacities deteriorate until he surrenders his

will, asks for help, and rejoins AA. In this series, Sipowicz

also tries to sponsor another department member. This plot depicts

the classic American disease model view of anyone with a drinking

problem. Many depictions of alcohol or drug problems as viewed

from the disease / recovery culture are demonstrated in popular

culture, from major motion pictures such as Leaving Las Vegas

(Figgis, 1995), Clean and Sober (Howard, 1988), and 28

Days (Thomas, Topping, & Grant, 2000), to television episodes,

to themes and images pervasive in most forms of media. Marketers

for brewers or distillers construct dream sequences of bikini

or Clydesdale teams on the air to remind the consumer that the

good life happens with alcohol. The consumer’s boring lifestyle

is shaken, not stirred. The capitalist prerogative to saturate

markets for profit continues, neither acknowledging nor taking

responsibility for the consequences. Whereas marketing discourse

serves to popularize drinking, alcohol problems are marginalized,

objectified, and relegated to the gaze of medical discourse. To

have a problem with alcohol is to be abnormal. The message is

that if you join a fellowship, abstain, and toe the line, perhaps

you will be redeemed, or at least viewed more acceptably, like

detective Sipowitz. How does this polarized perspective serve

the needs of persons who seek help? What is the role of the social

worker?

The field of addiction treatment has often been described

as a multidisciplinary setting, with competing etiological assumptions

and theoretical applications concerning addiction and therapy.

Since the inception of the Alcoholics Anonymous fellowship in

the 1930s, there has been significant progress in the development

of therapeutic methods to assist individuals with alcohol- or

drug-related dependencies (Baker, 1988; Berg & Reuss, 1998;

Blum & Roman, 1987; Chang & Philips, 1993; Roberts, Ogborne,

Leigh, & Adam, 1999a). Nevertheless, in North American culture

the concepts of the disease model and 12-step program treatment

dominate (Kaiser Foundation, 1997; Lender, 1979; Roberts et al.,

1999b). The culture of the disease model and the 12 steps of Alcoholics

Anonymous tend to predominate and marginalize alternative options

in northern remote communities.

For many who overcome an addiction habit, personal identity

relating to the process of recovery changes over time (Sommer,

1997). Others who face addiction and are adversely affected by

the dominant practices of the "recovery industry" (Peele &

Brodsky, 1991) find alternative ways of healing. Whereas society

often marginalizes the addicted, 12-step discourse often further

marginalizes those who do not conform to the accepted etiological

assumptions and resulting implications of the program (Granfield

& Cloud, 1996; Kearney, 1998a; Peele & Brodsky, 1991).

In spite of pressure toward conformity in the culture of recovery,

there are those who have success in overcoming addiction in their

own lives outside of a 12-step program or formal treatment (Anderson,

1994; Granfield & Cloud, 1996; Kearney, 1998a).

These stories of outsiders who eschewed the alcoholic-in-recovery

identity may reflect a self-perception based on strength and capacity,

turning away from a deficit identity. Some of these people tell

stories about learning to accept love, and about taking responsibility

not only for their potential worst, but for their best as well.

These persons seem to have developed a maturity and insight that

comes from years of personal work and growth. One participant

described a journey of discovery for the love within himself he

knew wasn’t afforded him as a child. Others describe their

families as their greatest strength, and that placing the family

first affirmed all of the love, support, and incentive needed.

Still others found that stepping out of the culture of recovery

was necessary to reclaim their creativity and find love. Other

qualities included demonstrations of strength, commitment, compassion

and consideration for others, and a potent determination to never

again give up their right to decide how to view the problem, or

the solution. Outsider recommendations invite reflection on what

it means to offer a no-harm practice; I believe we do no harm

whatsoever to our clients by identifying, amplifying, and celebrating

their strengths and capacities.

The information described from the experiences of these people

may have some interesting implications for social work practice.

These insights may also have meaning outside of the boundary of

discourse on alcohol problems and recovery, in that some of the

participants’ stories reflect a similar context of struggle

experienced by others, such as people with drug problems or smoking

and eating disorders.

Method

The research question I developed for this study was, how

do the experiences and needs of those overcoming addiction without

the 12-step / disease model culture impact social work practice?

I conducted an interview study with seven participants, using

a flexibly structured interview process in order to ensure participant

experiences would be documented in their richest detail, in relation

to the objectives of this research. The social constructionist

(where meaning is negotiated in discourse) design was intended

to invite participants into a "co-authorship" relationship, sharing

power and insights. This "co-authorship" function was supported

through a member-checking follow-up discussing and negotiating

the results of a retrospective analysis of problem severity and

a thematic analysis. The "co-authorship" intention of this research

is demonstrated through the use of participant quotation as much

as possible to ensure that experiences, theoretical developments,

arguments, and other insights could be credited to each of the

participants. The use of quotation would also serve to distinguish

my voice in the research from theirs - enhancing reflexivity,

as well as the credibility and transferability of the participants’

experiences.

Due to the politically controversial nature of this research,

I chose to conduct a retrospective analysis of problem severity,

in order to address the argument that participants did not suffer

from serious alcohol problems. I documented, through personal

review of interview transcripts, the extent of alcohol-related

problems apparent in each participant’s narrative. I developed

the units of measure for this analysis by adapting criteria from

the DSM-IV-TR, which is widely accepted in addiction assessment

discourse. I did not use the specific substance dependence criteria

from the DSM-IV-TR, to dispel any assumption that the participants

in this study could be diagnosed as substance dependent. This

analysis was limited to the presence of evidence within each participant’s

narrative that satisfied each of the adapted criteria.

I also conducted a thematic analysis; however it was

not my intention to attempt an exhaustive, complete description

of participant narratives. According to the social constructionist

view that meaning is a dynamic, ongoing negotiation within discourse,

the notion of completion is an unobtainable goal. I ended the

analysis development when the information from each participant

had been thoroughly reviewed according to the objectives I developed

reflecting the research question. Furthermore, I chose not to

overly interpret participant experiences through the thematic

analysis, preferring instead to use quotation from the participants

to allow their direct input to discourse with the reader. I believe

that this decision supports the integrity of the social constructionist

process, the wisdom of the participants, and the imagination and

critical judgement of the audience.

There were, in the end, seven participants. In retrospect,

I believe I could have found many more outsider interviewees

who would have shared their divergent success stories. Five interviews

were conducted face-to-face, one by telephone, and one via email.

Interviews (other than the email process) were audiotaped with

participant permission, and transcribed.

I managed to contact six of the seven participants for the

purpose of member-checking, after providing each of them a copy

of their transcribed interview and a draft of the thematic framework

I had developed. Each indicated they believed the model I used

accurately reflected her or his personal experience and perspectives.

One participant did not respond to my package nor to several phone

messages. Since this person had been provided several means to

contact me, had been briefed prior to signing the consent to participate,

and had been informed of my timeline, I assumed that her silence

did not constitute her withdrawal as a participant. She received

a copy of the finished thesis as mutually agreed.

The participants in this study have all experienced serious

alcohol problems, ranging from tolerance and avoiding important

events because of drinking, to withdrawal seizures. However, the

retrospective analysis was controversial for the participants.

Beth, (all participants have been given pseudonyms), provided

some feedback regarding this analysis which I believed reflected

a common concern participants had, over a process which involved

potentially pathologizing practices:

The criteria, like other mental health assessment tools, need

to take into account cultural, identity, and spiritual (including

personal values) aspects of the person being tested. I once had

a friend in class practice a new mental health assessment tool

on me. I asked her before I filled it out, "Do you want me to

answer like a client—like how I think it should be done,

or do you want me to answer honestly (including spiritual experiences)?"

She smiled and told me to answer honestly. So I did. My diagnosis?

Schizoid and dependent. Was she ever shocked! How could her test

say this? She had no clue as she thought that I was pretty functional.

I smiled back and told her that her test is designed for one culture

group and that she told me to be completely honest. The results

would have been different if I was answering like I thought I

should be (according to the culture behind the test design). How

true is that? Do I really need to be walking around with those

labels?

I think it is important to understand that I am

not a certified diagnostician, nor did I approach this analysis

from a completely neutral and objective position. Moreover, there

are obvious weaknesses in retrospective self-reports, particularly

concerning descriptions of character blemishes, and especially

regarding recollection of events over a decade old. It was my

intention that this exercise would provide evidence to caution

any assumptions trivializing the impact of participant histories

with alcohol.

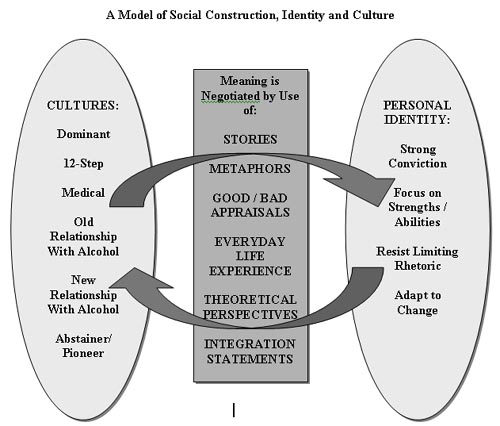

I attempted to create a framework to describe participant

experiences, and came up with a map (Figure 1) of the model I

developed for the purpose of organizing information from participants’

narratives:

Figure 1: A Model of Social Construction, Identity

and Culture

The model I developed is somewhat simplistic; I began with

the social construction concept, mapping the process of negotiating

meaning through discourse. Within the social construction process,

each interview had moments when the participant was her or his

own narrator. Consequently, each story was grounded by descriptions

of self, the "I," a dynamic focal point that I referred to as

personal identity. The participants’ conversations reflect

their present sense of identity, situated in the present, in context

to their story and their visions for the future. Their narratives

include stories of their experience with different alcohol-related

environments, which I have argued can be considered as cultures.

Different rhetorical frameworks such as the disease model and

the philosophy of the Alcoholics Anonymous fellowship also inform

discourse according to each view of people attempting to overcome

alcohol problems. I chose to describe these different perspectives

as cultures as well. For example, all participants spoke about

living in modern society, which I refer to as the dominant culture

(Fillingham, 1993; Rabinow, 1984), and about their "old relationship

with alcohol," which involved other people, rituals, practices,

and meaningful experiences. Whereas some participants speak of

a new life without alcohol (which I termed "Abstainer Pioneers"),

others speak about entering the fellowship of Alcoholics Anonymous

or other 12-step programs and later reclaiming their ability to

drink responsibly (which I termed "New Relationship With Alcohol").

Each of these situations involves other people, specific rituals,

practices, and meaningful experiences. Viewing these different

milieus as cultures has been accepted practice (Alasuutari, 1996).

Participant narratives provided information that suggested

some similar experiences. I have categorized experiences relating

to personal development and self-concept, such as "strong conviction",

"focus on strengths / abilities", "resist limiting rhetoric" and

"adapt to change". Other experiences that related to environment

and lifestyle I depicted as other cultures. Consequently, personal

experiences outside of the aforementioned cultures, such as the

12-step fellowship, could be recognized as contributing factors

in the mediation of identity.

Although the participants’ narratives resemble a generally

linear storyline, each person’s current identity has been

cumulatively impacted by their experience within each of these

cultures. Each of these cultures’ perspectives relating

to a person’s current relationship with alcohol, whether

abstinence or responsible use, is a mediating factor in the person’s

self-concept and their identity as they adapted to a new lifestyle.

Consequently, there is an ongoing relationship between personal

self-concept and different cultures, proportional to the person’s

experience, where meaning and consequent identity integration

are constantly negotiated.

For the purpose of this model and the analysis, I considered

the tools used in the mediation and expression of culture and

concepts of personal identity. Common methods I noted included

story, metaphor, good or bad appraisals, description of everyday

life, theoretical view and development, and the integrating statements.

Stories

Each participant’s narrative is a story in itself,

and within each narrative are many stories that help to situate

the person in his or her context, relating to the surrounding

culture that he or she was immersed in. These stories are the

allegories that inform the listener about the significance and

the meaning attached by the teller. They are the building blocks

of these people’s messages—their most vital tool in

communicating their experience. Consequently, participant stories

have been constructed in a manner specific to this research, and

would have been constructed differently in another situation.

Metaphors Reflecting Culture

The use of metaphor, a figure of speech where one word

or phrase is used to imaginatively but not literally replace another,

has been a significant and long-standing tool of qualitative research

(Gubrium & Holstein, 1999). In recovery culture, one can expect

to find a rich and seemingly endless number of metaphors (or codes

and ways of decoding cultural insiders’ constellations of

meanings). Each one is essentially a story unto itself; perhaps

it is an allegory with a moral or an in-your-face political message.

These metaphors are the shorthand of the political rhetoric of

recovery, which involves major transformations, such as the emergence

of a new identity, or profound shifts in the perceptions and practices

of everyday life. These metaphors can describe experience across

cultures, such as Joe’s:

Like my AA buddy, who is hard-ass, hard-core AA, has no

concept of his motives, although he’s learning. I can’t

help but love the guy. But we have another connection. We met

in school, when I was making a career change. We have a bond that

is from being in another trench. From being in the school trench¼

(Joe)

Or the recovery metaphors can be cloistered within a

culture, closed and cryptic, such as "A friend of Bill’s

(in reference to Bill Wilson, one of the founders of Alcoholics

Anonymous,)", "I took the pledge," "disease," "cunning, baffling,

and powerful¼ " "the word of recovery."

Such metaphors mark insiders to each other, and exclude those

who are outside of the culture of AA. Other metaphors can also

provide a powerful indicator about how the teller views his relationship

with the problem, the culture, or another relationship, such as,

"I was firmly captured and imprisoned by the alcohol"(John).

Good / Bad Appraisals

Appraisals are a significant part of the process of

moving from one culture to the next. They can provide a method

of preparation for migration similar to Smith and Winslade’s

work (1997), grounded in a number of practical models assessing

change, such as motivational enhancement (Miller & Rollnick,

1991) and the transtheoretical model (Prochaska et al., 1994).

Participant stories tend to indicate the level of commitment a

person has in a culture by the preponderance of positive appraisals

about the culture, relating to her or his identity. Judy spoke

about AA, and stated:

There’s no doubt it helped me, there’s no doubt about

that. It gave me people to be with that were trying to stay sober

too, which is what I needed and they supported me. And I think

that’s AA’s absolute biggest asset: people caring. And it put

me on some paths that I wouldn’t have explored if I hadn’t been

there, like spirituality. (Judy)

Stories reflecting outsiders’ ambivalence tend

to include more of a balance of good and bad appraisals for different

cultures. John gave a poignant example during a moment of reflection:

It makes me think back to that old story about AA, "once

an alcoholic, always an alcoholic," right? And I dismissed that,

at one point. But I need to know under new evidence, re-evaluate¼

Because I certainly don’t want to be going back to where I came

from. But saying that, that little voice of alcohol pops up and

says "maybe." (John)

Exit stories tend to reflect a shift of appraisals, with

the bad ones describing the culture being left behind, and the

more positive stories describing the culture they are moving to.

These positive appraisals often incorporate powerful reflections

of personal strengths and identity. Joe provides another excellent

example:

I stepped off into the world. I couldn’t stand the

hypocrisy. And you know what? At some point someone came along

and said to me, "Well, you know, these [meetings] are great, but

you get healthy here, and then you move on." And it was a seed

that they planted in my head. It was just a thought, just an idea.

It sat there, and suddenly I realized that I can’t stay

here forever. (Joe)

Participants who have settled into a new, possibly outsider

identity over time may begin to use positive appraisals about

former cultures, in proportion to the number of ideas from the

culture they have been able to incorporate into their new identity.

These appraisals are indicators reflecting the negotiation of

meaning between cultures and personal identity. Judy reflected:

And you know, to give AA their due I learned some good

things there, too. Like ways to deal with fear, and just all the

things life brings at you¼ the "one

day at a time," that’s good advice for anyone. (Judy)

Everyday Life Experience

Everyday life experience is the common ground between

personal experience, social and cultural context, and theoretical

perspectives (Alasuutari, 1992). John provided a poignant picture

of living in a world of hopelessness:

I tried suicide¼ because to

me at the end I termed it being between the proverbial rock and

a hard place. I took the gun out, I loaded it, I stuck it in my

mouth¼ and I couldn’t pull the Goddamn

trigger. I was scared of living and I was scared of dying and

I had nowhere to go¼ For me, even when

I wasn’t drinking, I could be out on a beautiful sunny day like

this walking down the road and it would actually look grey. It

was just dull. And that was my whole affect, right? I know, my

first sponsor, he said he used to watch me walk by and I never

looked up. I was watching my feet, walking down the road¼

(John)

These are the parts of a person’s narrative that provide

the witness with a window to life at that time, and provide an

illustration of how different cultures and political views look

and feel as normal, everyday experience.

Theoretical Perspectives / Developments

As a person migrates from one culture to another, explanations

become a natural part of integrating the process. It is noteworthy

to consider the migrating person’s explanations from the

perspective of the different cultures she or he is negotiating.

These explanations are the core of the social construction process.

This is where political rhetoric crashes into personal reality

and anecdotal truth. For example, George described his personal

model of addiction as, "I believe it’s a mental thing,

not a physical thing, in that sense. I figure that if it’s

mental then you have control over that, as a person." George’s

theory is his practical explanation of his success in abstaining

without help. If the reader reflects on his perspective in contrast

with the deficit-identity messages of the AA fellowship, the implications

of rhetoric on the person’s identity and attributions of success

become more apparent. Other statements that exemplify participants’

outsider theoretical views include "The pain and anxiety of

growing up in that household, that’s why I drank," (Joe);

"Alcohol, it isn’t the substance that’s the problem,

it’s the user" (Joe); "It’s about a number of things.

It’s about running, it’s about not facing reality.

It’s about fear. It’s about pain" (Claire).

Integration Statements

Integration statements are affirmations regarding self-concept

in relation to cultural influence. These are the statements that

reflect upon what a person’s story is telling her or him

about who she or he is as a person. Many stories end with integration

statements, whether these stories are allegorical or about the

living journey itself. Integration statements are often reflective

potent descriptions, with a focus on what is and leaving behind

what isn’t. These statements can also reflect fundamental

understandings about need, hope, and acceptance, and can be spiritual

affirmations: "Let’s say I was an alcoholic" (George);

"I’m one of the strongest people I know" (Joe); "The choice

I made I feel great with," and "I didn’t make this

decision thinking everybody was going to accept it. I didn’t

make it for them, I made it for me" (Claire).

I have identified and described these different processes

of negotiating and expressing meaning as if they were mutually

exclusive; obviously this is not the case. These processes are

more than the sum of their parts, and they are interconnected;

it would be unlikely to have integrating statements without inferring

some theoretical view, good or bad appraisals locating self-concept

in relation to political rhetoric, or without the use of metaphor.

Wrapping the entire context of a person’s identity and journey

into the label "story" seems to trivialize the person’s

experience and meaning. A story is just one description of the

complexity of one’s experience. It is the profound nature

of the experience that makes these stories so rich and provocative.

Culture

Each participant story of experience reflects more than

one culture, and some reflect the influences of more cultures

than are within the scope of this study, including cultures of

ancestry, career (for example, families of railroaders), or gender.

The process of describing the different cultures in the participant

stories resembles a general map of the journeys the participants

took, implying an archetypal story worthy of Ulysses’

narration. However, "the map is not the territory." Although the

description of the different cultures is offered sequentially

as a general narrative roughly similar to these participants’

experiences, this framework should not be considered as a grand

story but rather as a reflection of each participant’s identity

development in relation to the impact of different cultures over

time. Each participant took her or his own journey toward a better

identity.

Participant Recommendations to the Helping Profession

Participants offered their own ideas about what they

felt professional practitioners need to know in order to help

others struggling with addiction problems. Here’s what they

had to say.

Joe’s response addressed his own experiences with counsellors:

If you choose to be in social work, or a counsellor or

something, you’re choosing to help people. Then you better

have helped yourself.

¼ And so as a professional¼

when you are the resource broker, and you are trying to allocate

resources, how do you fit a person like me into that system? I

don’t know. Advice? I still honestly have to say, I think

[pause] you need to have done some of your work. No perfection.

And suspend the judgement. I think that if you have done your

own work I think that you can easily suspend your judgement.

¼ That’s been my absolute best

experience, a group situation. It was a project. It had a beginning,

a middle, and an end. Okay? And then you move forward. And the

worst part about AA is that, here I am—I want to quit drinking

and then there’s the rhetoric that these people are trying to

pump into me, that, "Oh, you’re here for life." Why the hell do

I wanna be around a bunch of hypocritical people for the rest

of my life, with the threat that if I have another drink I’m going

to die? I mean, how coercive is that? A beginning, a middle, and

an end. And then you have to step out and try what you’ve learned.

(Joe)

Joe implied the need for professional helpers to understand

his theoretical framework: that addiction is merely a destructive

solution for underlying issues. While Judy provided some hints

at her own etiological assumptions about addiction, her advice

is simple:

I’ve got a bit of a biologist, science kind of slant with

my work, and I don’t believe it’s a disease until I have the proof.

You know what I mean? I think that definitely there is a

chemistry difference between people with addictions and others.

But that’s all addictions, be it whatever. And I think that

hopefully, eventually medical science will be able to address

that. And not by Band-Aids; you know, giving people mood-altering

drugs and so on, but by giving people naturopathic diets that

give them whatever’s missing that causes that imbalance.

That’s what I’d like to see; that would be my answer

to your magic wand question.

You asked a question about what could help doctors and psychologists

and social workers and people like yourself to do better? The

only thing I have to say, is give people the room to do whatever

works. (Judy)

Judy’s last statement implies the need for

client-centred practice; giving people the room to do whatever

works requires providing therapeutic space to respect the client’s

perceptions of problems, solutions, goals, and outcomes.

George’s response to the question, "What do you think

that professional people (social workers, therapists, and the

like) need to know from your experience about overcoming addiction?"

was powerful:

I think [pause] as witnessing the Ministry’s [of

Children and Family Development] problems that they have—they’re

understaffed, they’re underpaid, and they have one social

worker for two handfuls of kids. They cannot protect them all,

they cannot be eyewitnesses to everything that goes on in the

houses were they are.

They need somebody [pause] to go around to these places and

[pause] take every little issue that these kids have and take

it seriously. [pause] Don’t take it with a grain of salt.

Don’t take it that you’ve heard it [pause] from other

kids or whatever. Listen to the kid, ’cause the kid is trying

to tell you something. And if it is alcohol-related there is a

reason why, there is a reason this kid is drinking at 12, there

is a reason this kid is doing drugs, there is a reason she is

on the street selling her body.

And it’s not even in the foster homes; it’s in

every home. Like I know friends of [name] that are, you know?

You just want to scream, at some of the shit that goes on with

their parents, you know? And what can you do about it? I know

society has come along way from [pause] listening to your neighbours

fight and get into a fistfight and the husband is yelling at the

wife and all’s you do is close the window. But it still

goes on, you know?

I just [pause] I just wish that the kids that are in trouble

would get help earlier. A lot of them. Because nine times out

of ten, when they do get help it’s too late.

I wish that [pause] that somebody would have taken an interest

in me as a young child and done that sort of stuff with me. I

mean, somebody I could look up to and say he does drink and party

and he’s got a good home life and [pause] he’s got

a job [pause] and you know [pause] something that I could look

forward to that way. Where all I had were my friends, and alcohol

was their buddy as well as mine¼

Yup that was the gist of it. I feel that [pause]

that kids today, they’re probably in worse than I ever was

because before when I was going to school, you know everybody

partied on the weekends and stuff, but drugs wasn’t the

problem that it is today. Kids, you know [pause] you got to get

to them early in my eyes. (George)

George’s response reflects his values about nurturing

children, which he believes needs to be the principal focus for

preventing or reducing the harm of substance abuse.

Gina’s answer, in response to why she decided to participate

in this research, reflected a holistic worldview, addressing everything

from the desire to live to self-care:

You’re going to pass it along, and maybe somebody will

benefit from it, they’ll be open about themselves, and, just spewing

your guts out about what your problem is. Don’t be afraid, don’t

try and hide it. You want to do something. Everyone wants to help

themselves, nobody wants to die. Nobody wants to.

Wherever there’s life there’s hope, and I’ll

always remember that. And that’s what these people should

be saying. "Let’s see about what we should do." Just remember

that they don’t want to die. You know, there’s hope.

Physical health is very important, three meals a day, especially

for someone that is drinking, that doesn’t want to quit,

they should have three meals a day, and take vitamins. And when

you do decide to quit drinking, you have a better chance of survival,

physically when you do go into detox. It’s very important

to have your daily nourishment. And the more you eat the less

you drink. And then even if you do drink just as much, the food

helps to absorb the alcohol.

I think if your body’s well nourished, you’ll

go out and do things; be more active. And when you’re not

eating properly you’re sitting there with a can of beer

or something, and neglecting the kids. If you’d have kept

your health up you could be doing things with the children. Well,

my children are my pride! (Gina)

Gina’s response reflects the need to recognize and develop

goals with people in a holistic manner, addressing issues from

physical health to a healthy environment, parenting, and hope

that provides motivational and spiritual grounding for a person

to reclaim a life worth living.

John’s insights underscore the need for patience, persistence,

and empowering people who are overcoming alcohol problems:

I think the most important thing I think for people working

with people with alcohol and drug problems is it’s a process.

Relapse is normal. I’m trying to think if I know of even

one person who never had a relapse. Including myself up till the

time I actually got it, like I tried to quit a hundred times.

You know? It didn’t work. ’Course I wasn’t trying

to get any support or figure out a way to do it, I was just going

to stop drinking.

Well that didn’t work. So I think it’s important

to understand that it’s a process and it takes time and

it’s the whole piece of the person has to be with it. It

has to be integrated with their physical well-being, their spiritual

life, or getting some sort of spiritual connection; [pause] not

necessarily in the AA sense, but just in the sense of becoming

comfortable with self.

Because if you’re not comfortable with yourself you’re

going to take something to change how you feel. I think there’s

a lot of core stuff around that and people need to be supported

through it and it can be a very frustrating experience for people

trying to work with them who want quick change cause it doesn’t

happen that way. It just does not happen. So patience and caring.

Caring for them all the way through it and if you do that long

enough you’re going to see some of them change.

And give them power. Give them their power. And that’s

one of the things that AA takes away, it dis-empowers. Turn your

power over to this higher power which means you’re weak

and powerless so, and I think people need to get control of their

lives and I think that’s part of what happens after five

or six years; they take their power. They get on with their lives.

That doesn’t mean that you can’t have a spiritual

connection or whatever it is but it also means that you’re

aware of your own, where you do have some power. (John)

John’s advice reflects Gina’s ideas about

working from a holistic framework, and Joe’s theoretical

view that addiction masks underlying issues. I infer that his

thoughts about patience and perseverance, about the non-linear

process of recovery, and the need for empowerment suggest client-centred

approaches. "Give them power" implies the concept of therapy as

a political act, a perspective amenable to feminist and narrative

therapeutic frameworks.

Claire, responding to the question, "Imagine that you have

been given a magic wand, which will help you create the ideal

circumstances for people like yourself to resolve their addiction

problems. What would you like to do?" demonstrated her insight

as a practitioner:

What would I do? Oh wow, that would be so much fun! I

would have everything in one centre. And what I mean by that is

after they were all detoxed and stabilized and all that kind of

stuff, instead of just preaching the 12-step programs, going through

the little alcohol and drug system during recovering planning,

I would have them meet people in the programs that were¼

. Say the 16-step empowerment program because it’s a lot

different than a 12-step program. And yet they would meet the

12-step program people. They would meet people who are doing what

I’m doing today. Like harm reduction I guess would be the

word cause I can’t really find a word for it. Yeah, so they

would have all the choices, all the time in the world right? You

can learn about them all, and they all have their own little workers

of course, [laughter] cause we got lots of money. One-to-one here,

who had no opinions except to totally inform them and completely

empower them to make their own choices. Then I think people would

get recovery, but it costs a lot of money. Because I think that

when we’re making choices for other people we’re not

empowering them so we see them over and over and over again. But

I also think they don’t have the money to do that, right?

Well, no magic wand? The next best thing would be what I

try to do. Is still informing people. Information taking, understanding

people for where they’re at I think is the key. I believe

that referral is very important. I mean, I do recovery plans with

20 people a day. And they listen to me and most of them just do

whatever because they don’t know. So if I’m being

the best I can be that day, because I’m not overworked,

without the magic wand I guess, just time and really informing

them. Instead of saying, "Well this is our system of care, you

should go from here to this 28-day program, support recovery program,

then this 30-day treatment program, and ¼

" Because that’s what’s there.

Everybody is an individual. Yeah. If my experience could

stop those people [professional practitioners] from clumping people

with addiction issues into one certain criteria. I mean, especially

if you’ve been in the field for a while it’s hard

as human beings not to expect people to be a certain way. So that

would be for right across the board for them to absolutely listen.

And understand a person’s individuality, because if that

happened, then I guess decisions based off that would be thoroughly

off the person’s needs and only the person’s needs.

And not what has been normal or accessible or affordable. (Claire)

Claire’s professional advice to colleagues strongly promotes

client-centred practice: to eschew assumptions that clump clients

into one category, to understand a person’s individuality, to

absolutely listen, completely inform, and completely empower.

Claire recognizes the authority of her professional status, but

argues that decisions need to be made based only on the person’s

needs, which I believe would take priority over the dominant discourse

of institutional privilege. Claire’s belief in referral implies

a professional duty to help situate clients back in their lives

with resources that fit their needs.

Beth clearly provides an invitation for practitioners to

accept and support clients who need to find their own path to

a better life:

The ideal circumstances for people like me to resolve

addiction problems would be to work with someone and /or a group

that is not going to try and peg me into an already set pattern

of use and that has the attitude of exploring who I am, what I

need, what and how to be happy, healthy and fulfilled in ways

that are not going to hurt me or others. A program of some sort

that teaches ways of living in the world. This scenario would

be expanding, empowering, and full of experiments. It would be

far removed from disease and a continual alcoholic identity.

Professional people need to know how to respect and honour

my experience in overcoming addiction. This means cultivating

an attitude of being present, curious, and knowing how to listen.

They need to be quiet, focused, and aware of their own feelings,

programming, and experiences. The helper’s reference point

may not be true for the individual who is sharing.

As a final point, I believe healing from an addiction involves

accurate knowledge, the permission to change strategies, refresh

old ideas, and most importantly people who are genuine and who

can listen without judgement. (Beth)

Beth’s advice also promotes self-determination reflecting

client-centred practice, but with a distinctly postmodern flavour.

She suggests a focus involving a counsellor’s intimate self-awareness,

genuineness, and listening without judgement; and a process that

eschews deficit rhetoric and promotes experimentation and exploration

of needs, identity, and fulfillment in the context of the world.

When I reflect on these persons’ narratives and their

suggestions intended for the professional practitioner reading

this work, I believe they are asking to be listened to and respected

as individuals, and to not be judged. I believe they meant that

they’d like their issues to be treated in a manner that

respects their individuality, and not as problems that fundamentally

limit how they should see themselves. I believe they respect practical

solutions for alcohol problems, including abstinence, especially

in the beginning of the process of reclaiming their lives.

Theoretical Implications of this Research

Participant experiences challenge a number of "one size

fits all" theoretical tenets grounded in the etiology of alcoholism

as a disease. Specifically, in spite of personal histories of

serious alcohol problems prompting professional assessment and

referral to AA, some participants’ current relationship

with alcohol is not characterized by compulsive use, loss

of control, nor progression. Four out of the five participants

who chose to experiment with controlled drinking have managed

to do so successfully for a period of time ranging from two years

to more than a decade. These four participants indicated that

they control their alcohol consumption and have not experienced

compulsive urges or negative consequences attributed to their

drinking. Consequently, there is no evidence of the phenomenon

of progression. The fifth participant, John, who was ambivalent

about his alcohol use, has made some significant changes, is now

abstaining (without using disease / 12 step rhetoric), and enjoying

a range of recreational and social activities.

Consequently, participant narratives challenge the primary

tenet of the medical model of alcoholism: that it is an incurable

disease. Disease concept proponents would argue that these four

persons have demonstrated merely that they are not alcoholics.

Although this is a possibility, this argument does not acknowledge

the serious nature of each participant’s past troubled relationship

with alcohol. Nor does this argument address the fact that professionals,

and / or fellowship members themselves supported these participants’

inclusion into 12-step culture at one point, thereby accepting

them as "recovering alcoholics." In fact, this argument tends

to reflect the political nature of the disease concept, emphasizing

that disease-focused theory has been constructed in a manner that

prioritizes safest outcomes and risk reduction over self-determination,

strengths, and capacities.

Applications of disease-focused theory (AA, 1976; American

Society of Addiction Medicine, 2000; Canadian Association of Addiction

Medicine, 2002; Diamond, 2000; Gorski & Miller, 1986; Jellinek,

1960) can have a totalizing feel (Le, Ingvarson, & Page, 1995).

Alcohol misuse is often seen as symptomatic of the progressive

illness of alcoholism, requiring abstinence and AA. Mandating

a rigid prescription for least-risky behaviour does not necessarily

honour individual capacities, as attested by the participants

in this research. In respect to the disease model, these participants

demonstrate that not all persons with serious drinking problems

are alcoholics, and that 12-step programs may not suit the needs

and preferences of all persons with a history of serious drinking

problems.

Participants in this study seem to be more effectively supported

using harm reduction perspectives, which also promote safety,

but in the context of individual needs and preferences. While

harm reduction rhetoric does not generally recommend experimenting

with high-risk substances, this perspective accepts the fact that

risky behaviour does occur. Harm reduction principles support

ideas such as using personal guidelines and limits to manage alcohol

use, as well as establishing criteria to assess and, if necessary,

abandon the experiment with controlled.

Practice Implications of this Study

This research presents several implications for social work

practitioners in the addiction field. Participant narratives illustrated

a dilemma regarding assessment: most of the "new relationship

with alcohol" participants were referred to 12-step fellowships

by professionals. How do we effectively distinguish alcoholics,

for whom 12-step referrals are appropriate, from other problem

drinkers? Perhaps there are more effective methods of assessing

client needs and preferences.

Participant narratives also illustrated a potential dilemma

regarding resources. Claire provided an example of an alternative

support community through her participation in a 16 step empowerment

program (Kasl, 1992). In small, northern, and remote communities,

professionals may refer clients to 12-step or other resources

out of immediate necessity, lacking other resources that might

provide a more fitting or effective service. In other words, ethical

practice would indicate referral to the only resources available,

a better-than-nothing scenario. Although all of the participants

who attended a 12-step program in this research indicated gratitude

for the program’s support in gaining a period free from

abusive drinking, there was also significant interest in the development

of accessible alternative resources and support systems.

Advice offered to social workers by participants suggests

a preference for client-centred practice. Client-centred approaches

are supported by the codes of ethics for social workers and addiction

counsellors (British Columbia Association of Social Workers, 1999;

Canadian Association of Social Workers, 1994)

Major Contributions of this Study

This study has provided evidence of possibility. Participants

with serious alcohol problems in their past quit drinking without

using deficit rhetoric associated with the disease model, or they

abandoned the rhetoric and have successfully managed their drinking.

These experiences have happened; this proves that they are a real

possibility. Since my decision to end the information-gathering

phase, I have heard from more people about friends or family members

who have experiences similar to those of the participants in this

study.

This study has made several contributions to the field of

addiction research and social work practice. First, it has documented

the experiences of people who have been marginalized by the rhetorical

assumptions of dominant theoretical frameworks. Second, it has

exposed dominant rhetorical deficit-focused perspectives as only

one way of viewing people’s experiences. Participants’

narratives in this study reflect multiple knowledges, journeys,

roads, and uncharted territories. Third, this research provides

a social constructionist model depicting the negotiation of meaning

between cultures of knowledge, which contribute to the transformation

of identity. This model may have some utility for understanding

experiences of people who choose to live in theoretically uncharted

territories. Finally, this study has drawn several implications

for social work practice, regarding assessment procedures, therapeutic

approach, and resource development.

Conclusion

This study has described the experiences, needs, and preferences

of people who have chosen to address alcohol problems beyond the

rhetoric of the disease model and 12-step framework. In the process,

some of these people have faced marginalization as a consequence

of blazing their own trails through theoretically uncharted territories.

Their narratives helped to explore issues surrounding deficit-focused

paradigms of addiction treatment. They participated in the development

of a social constructionist model to help understand discourse

relating to their experiences. Their narratives demonstrated how

overcoming serious alcohol problems can involve multiple knowledges,

journeys, roads, and uncharted territories in the quest for a

more fulfilling, more meaningful life. Several implications for

social work practice were discussed regarding assessment, therapeutic

approach, and resource development.

One of the most significant concepts of the discipline known

as cultural studies is the idea that knowledge is relative; there

can be no end point. Consequently, there is no conclusion for

this research into alternative experiences and journeys relating

to alcohol problems. I hope that this information will serve to

invite the possibility of openness regarding how we in the helping

profession see and serve the people we are asked to assist.

In summary, the experiences of the participants in this study

contradict rhetorical assumptions that are often the foundation

for strategic practice in the addiction field. Perhaps the best

way to address this point is through the commonly used pickle

metaphor. Essentially, cucumbers can become pickles, but never

vice versa. Yet this research provides evidence of pickles "reclaiming

cucumberhood." This research also clearly documents participants

who were able to stop the pickling process on their own without

professional or conventional help. Finally, this research supports

the social constructionist view of pickles and cucumbers as linguistic

conveniences that serve the viewer more than the person under

gaze.

The persons in this study said they were willing to volunteer

their experiences, providing that their stories might offer hope

and assistance for one other person out there. I respect and reflect

on their sentiment as a personal challenge, and respectfully invite

you, the reader, to consider their ideas when reflecting on your

own practice.

References

AA. (1976). Alcoholics Anonymous (Vol. 3). New York: Alcoholics

Anonymous World Services.

Alasuutari, P. (1992). Desire and craving: A cultural theory

of alcoholism. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Alasuutari, P. (1996). Theorizing in qualitative research: A

cultural studies perspective. Qualitative Inquiry, 2(4),

371–385.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical

manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington,

DC: Author.

American Society of Addiction Medicine. (2001, August 18). The

definition of alcoholism. Retrieved November 30, 2002, from

http://www.asam.org/Frames.htm.

Anderson, S. C. (1994). A critical analysis of the concept of

codependency. Social Work, 39(6), 677–685.

Baker, T. B. (1988). Models of addiction: Introduction to the

special issue [entire issue]. Journal of Abnormal Psychology,

97(2), 115–117.

Bannerman, B. B. (2000). A search for healing: A phenomenological

study. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Northern

British Columbia, Prince George, BC.

Berg, I. K., & Reuss, N. H. (1998). Solution step by step:

A substance abuse treatment manual (1st ed.). New

York: W. W. Norton.

Blum, T. C., & Roman, P. M. (1987). Social constructions

and ideologies of substance abuse [entire issue]. Journal of

Drug Issues, 17(4).

British Columbia Association of Social Workers. (1999). Code

of ethics. Vancouver, BC: Author.

Brooker, P. (1999). A concise glossary of cultural theory.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Canadian Association of Social Workers. (1994). Social work

code of ethics. Ottawa, ON: Author.

Canadian Society of Addiction Medicine. (2002, November 27).

Definitions in addiction medicine. Retrieved November 30,

2002, from www.csam.org/index.html.

Chang, J., & Phillips, M. (1993). Michael White and Steve

de Shazer: New directions in family therapy. In S. Gilligan &

R. Price (Eds.), Therapeutic conversations (pp. 95–111).

New York: W. W. Norton.

Denzin, N. K. (1993). The alcoholic society: Addiction and

recovery of the self. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Diamond, J. (2000). Narrative means to sober ends: Treating

addiction and its aftermath. New York: Guilford Press.

Figgis, M. (1995). Leaving Las Vegas [Motion picture].

United States: Metro Golden Mayer Studios.

Fillingham, L. A. (1993). Foucault for beginners. New

York: Writers and Readers Publishing.

Furman, B., & Ahola, T. (1992). Pickpockets on a nudist

camp: The systemic revolution in psychotherapy. Adelaide,

Australia: Dulwich Centre Publications.

Gorski, T., & Miller, M. (1986). Staying sober: A guide

for relapse prevention. Independence, MO: Herald House/Independence

Press.

Granfield, R., & Cloud, W. (1996). The elephant that

no one sees: Natural recovery among middle-class addicts. Journal

of Drug Issues, 26(1), 45–62.

Gubrium, J. F., & Holstein, J. A. (1999). At the border of

narrative and ethnography. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography,

28(5), 561–573.

Gusfield, J. R. (1996). Contested meanings: The construction

of alcohol problems. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin

Press.

Holst, J. A., (2003a, January 18). Advertising mascots: The

Swedish Bikini Team. Retrieved January 18, 2003, from http://www.tvacres.com/admascots_swedishbikini.htm.

Holst, J. A., (2003b, January 18). Animal mascots: The Clydesdales.

Retrieved January 18, 2003, from http://www.tvacres.com/horses_advertising.htm.

Howard, R. (1988). Clean & sober [Motion picture].

United States: Warner Brothers.

Jellinek , E. M. (1960). The disease concept of alcoholism.

New Haven, CT: Hillhouse Press.

Kaiser Youth Foundation. (1997). Directory of substance abuse

services in British Columbia. Vancouver, BC: Kaiser Youth

Foundation & Alcohol and Drug Services, Ministry for Children

and Families.

Kasl, C. (1992). Many roads, one journey: Moving beyond the

12 steps. New York: Harper Collins.

Kearney, M. (1998). Truthful self-nurturing: A grounded formal

theory of women’s addiction recovery. Qualitative Health

Research, 8(4), 495–513.

Kytasaari, D. (Producer). (2003). TV Tome. Retrieved January

15, 2003, from http://www.tvtome.com.

Le, C., Igvarson, E. P., & Page, R. C. (1995). Alcoholics

Anonymous and the counselling profession: Philosophies in conflict.

Journal of Counselling and Development, 73, 603–609.

Lender, M. E. (1979). Jellinek ’s typology of alcoholism:

Some historical antecedents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol,

40(5), 361–375.

Marlatt, G. A. (Ed.). (1998). Harm reduction: Pragmatic strategies

for managing high-risk behaviours. New York: Guilford Press.

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (1991). Motivational interviewing:

Preparing people to change addictive behaviour. New York:

Guilford, Press.

O’Hanlon, W. H. (1993). Possibility therapy: From iatrogenic

injury to iatrogenic healing. In S. Gilligan & R. Price (Eds.),

Therapeutic conversations (pp. 3–21). New York: W. W. Norton.

Peele, S. (1989). Diseasing of America: Addictions treatment

out of control. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Peele, S., & Brodsky, A. (1991). The truth about addiction

and recovery. New York: Fireside.

Prochaska, J. O., Norcross, J. C., & DiClemente, C. C. (1994).

Changing for good: A revolutionary six-stage program for overcoming

bad habits and moving your life positively forward. New York:

Avon Books.

Rabinow, P. (1984). The Foucault reader. New York: Pantheon

Books.

Roberts, G., Ogborne, A., Leigh, G., & Adam, L. (1999a).

Best practices: Substance abuse treatment and rehabilitation.

Ottawa, ON: Office of Alcohol, Drugs and Dependency Issues, Health

Canada.

Roberts, G., Ogborne, A., Leigh, G., & Adam, L. (1999b).

Profile: Substance abuse treatment and rehabilitation in Canada.

Ottawa, ON: Office of Alcohol, Drugs and Dependency Issues, Health

Canada.

Smith, L., & Winslade, J. (1997). Consultations with young

men migrating from alcohol’s regime. In M. Raven (Ed.),

New perspectives on ‘addiction’ (Vols. 2 & 3, pp. 16–34).

Adelaide, Australia: Dulwich Newsletter.

Sommer, S. (1997). The experience of long-term recovering alcoholics

in Alcoholics Anonymous: Perspectives on therapy. Alcoholism

Treatment Quarterly, 15(1), 75–80.

Thomas, B., Topping, J., & Grant, S. (2000), 28 days

[Motion picture] United States: Columbia Tristar.

Truan, F. (1993). Addiction as a social construction: A postempirical

view. Journal of Psychology Interdisciplinary & Applied,

127(5), 489–500.

White, M. (1993). Deconstruction and therapy. In S. Gilligan

& R. Price (Eds.), Therapeutic conversations (pp. 22–61).

New York: W. W. Norton. |