I remember when Mary came to live with us. It was spring and the snow had melted

quickly that year, causing rivers to overflow their banks. The old bridge at

Kemp Landing washed away, but it was pretty rickety already. It got stuck alongside

Fred Ducharme’s dock, trees and things piling up against it. He lashed it on

as best he could, thinking he’d extend his wharf by a good twenty feet, but

the force of the water ripped everything off and he ended up with no dock at

all.

Mary and Pa almost didn’t make it home from the wedding, the roads being so

bad. Pa’s old Chevrolet got stuck in the mud; they had to go back later with

a team of horses to pull it out. Mary and Pa hitched a ride on the back of August

La Fleur’s pig wagon, wedding suits and all. Mary thought it was great fun.

She was like that.

Frank Jackson,

my Pa, married Mary Percy on March 10, 1931, in Battle River. But it wouldn’t

have happened if it hadn’t been for me. Pa was too shy to ask Mary himself,

but I could tell he sure liked her a lot. He was always bringing patients to

her, just so as he could visit. He even bribed Moostoos, our farm hand, into

letting Pa take him down to see Dr. Mary for an ingrown toe nail. Moostoos would

just as soon have chopped the toe off himself. Lots of fellows were keen on

Mary. She was always invited to one party or another. She sometimes stayed up

all night dancing. I remember the women talking at Keg River Sunday socials,

scandalized by Mary’s many gentlemen friends. I knew if Pa didn’t do something

quick, someone else would snap her up.

Frank Jackson,

my Pa, married Mary Percy on March 10, 1931, in Battle River. But it wouldn’t

have happened if it hadn’t been for me. Pa was too shy to ask Mary himself,

but I could tell he sure liked her a lot. He was always bringing patients to

her, just so as he could visit. He even bribed Moostoos, our farm hand, into

letting Pa take him down to see Dr. Mary for an ingrown toe nail. Moostoos would

just as soon have chopped the toe off himself. Lots of fellows were keen on

Mary. She was always invited to one party or another. She sometimes stayed up

all night dancing. I remember the women talking at Keg River Sunday socials,

scandalized by Mary’s many gentlemen friends. I knew if Pa didn’t do something

quick, someone else would snap her up.

Me and Arthur were out back fixing the chicken coop as best we could. Arthur

had forgotten to latch the door, and a fierce wind had ripped it off, hinges

and all. That’s when I got the idea to hammer a nail clean through my hand.

Arthur went screaming to Pa. He always was squeamish. Pa took me down to Dr.

Mary, five hours through a snow storm, and another five hour wait till she returned

from delivering a baby. By then Pa had pretty well stopped the bleeding. Mary

bandaged me up proper, and invited us to supper, though it was Pa who ended

up doing the cooking. I remember the look of anger, fear and pain on Pa’s face

when I said to Mary, "Pa sure would like to marry you." Anger at me,

fear of being made a fool of, and pain of rejection. I’ll never forget the laughter

in Mary’s eyes, behind those funny, round spectacles. In her proper English,

she replied, "I’d be delighted." Pa grabbed her round the waist and

they whirled around the room. I just curled up on Mary’s bed, exhausted from

the trip, and fell asleep.

Pa was a gentle man. I don’t remember him ever so much as raising his voice

at us. The disappointment that filled his eyes when we did something wrong was

worse than being taken to the wood shed with a switch. Ma thought Pa was too

soft on us boys. She had a big wooden spoon in the kitchen that she used as

often on our back sides as for stirring goulash. I remember once when Arthur,

a year younger than me, forgot to close up the chickens. That night, every last

one of them was eaten by foxes. Ma was furious. She took our Arthur over a chair,

and gave him a good hiding. I sat on the floor between the wood stove and the

cupboard, too scared to move. I still remember Arthur’s look, his eyes appealing

to me for help. I’ll never forget it. It was the same look he gave me ten years

later when he was taken down by German gunfire in France. But I couldn’t go

back for him. I sat in that damn, muddy trench all night, the pouring rain chilling

me to the bone. By morning he was dead.

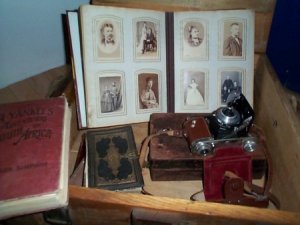

I don’t remember Ma ever being happy. Maybe it was her stern Germanic character.

Maybe it was her bitter disappointments in life. Her people had been wealthy

and influential in the old country. I was named after her Uncle Louis who had

died a hero’s death in the Prussian army. She tried to instill some pride into

us, showing us her precious family photo album. Illustrious ancestors that looked

foreign to us in their strange clothes. It was a world we could not understand.

The photographs stopped when she and her family emigrated, reduced to farming

in the American mid-west, too ashamed to add pictures, or too poor. Her disappointment

at seeing us boys grow up wild in Keg River must have been overwhelming. She

never said anything, but I could tell by the tight, thin line of her mouth.

I think she found little comfort in the Bible given to her by two elderly English

missionaries passing through Keg River, eager to lighten their load on their

way back to civilization. Ma had it hard up here, raising two boys pretty much

by herself. Pa was gone most of the time, wintering out with the cattle, or

running the trading post. It was a loneliness she never got used to. Ma grew

more and more bitter and took it out on us boys. I sometimes think it was a

relief for her to die – she saw no other way out of this life.

Mary was always cheerful, even when she had to get out of bed in the middle

of the night to ride into a cold winter storm. I always saddled Dan for her

while she got ready. It gave me an ache in my heart to see her disappearing

in a swirl of snow. I wished I could have gone with her. The only time I ever

saw Mary cry was when old Dan died. She stayed in the barn with him all night.

I snuck in before the sun was up, and heard her talking to him, tears trickling

down her face. I knew then he was done for. I quietly slipped out so as she

wouldn’t see me. Pa was out bringing a load of pelts down to Peace River with

Arthur, so I dug a hole for Dan by myself. It took me all day.

When Mary came to live with us, she brought her gramophone and a stack of

books. She loved reading and, curled up in the window seat Pa made for her,

often forgot to cook supper. But we didn’t mind. Her family sent books for us

boys, too. Our favourite was "A Yankee’s Adventures in South Africa."

Arthur made me read that book over and over again to him, till the pages were

loose. He pictured himself as the fearless hero, Harry Lovejoy, "the very

picture of health, of strength, of noble, young manhood." How many times

Arthur made me reread that line! I tried to sneak away to the treehouse so that

I could enjoy the book by myself. I was partial to the heroine, who thought

it was grand to nearly be drowned in a sudden downpour. She was my kind of girl.

Mary had boxes of photographs she had taken. Me and Arthur used to study them

for hours, sitting up in the old willow tree out back. We especially liked the

ones from her trip to the mountains. We dreamed of becoming famous mountain

climbers, and practiced going up and down the steep banks along the Keg River,

tied together on a rope. Sometimes Arthur slipped, pulling us both down. Mary

took pictures of us too. I still keep one of me and Arthur on my night table.

It brings back memories of times gone by, of two young, carefree boys who explored

the forests and rivers of Keg River all summer long. One year, me and Arthur

lashed together a raft from old trees lying along the shore, and pretended we

were pirates. By the time we got hungry, we were so far down river, with no

way of getting back other than walking. We picked raspberries on the long walk

home. Ma was madder than heck when we finally got back, well after dark. The

next day she made us scrub the earthen floor with ox blood till it gleamed.

Arthur followed me everywhere, and tried to do everything I did, even though

he was younger, and small for his age. I tried to swim Keg River once, to see

if I could make it across. The current was strong and the water ice-cold. I

was almost halfway, and already tired, when I heard a shout behind me. Arthur

was struggling, being swept helplessly downstream. It was all I could do to

get hold of him and drag him ashore. We both lay exhausted on the muddy banks,

too spent to speak. When I went down to Calgary to enlist, he followed me. I

tried to send him back, but he lied about his age and got into the regular army.

I gave up hopes of being an Air Force mechanic, and signed up with him. I had

to keep an eye on him.

Mary let me use her camera, and taught me how to take good pictures. She gave

it to me when I turned sixteen. I carried that Balda everywhere, and

took pictures of everything that moved. At night I carefully put it away in

my wooden box under the bed. Not even Arthur was allowed to touch it.

After the War, I stayed on in Europe and worked as a freelance photographer,

visiting concentration camps. People didn’t want to believe it was true, but

I saw it with my own eyes. I tried to fill my days with their pain, in order

to block out my own. When I returned to Canada, I got a job with a small, local

paper in Edmonton. I never did marry. I think that my little boy’s heart was

lost when Mary came to live with us.

Louis Jackson

Jackson, Frank. A Candle in the Grub Box.

Victoria: Shires Books,

1977.

Victoria: Shires Books,

1977.

Jackson, Frank. Jam in the Bedroll.

Victoria: Shires Books,

1979.

Victoria: Shires Books,

1979.

Jackson, M. Percy. Suitable for the Wilds: Letters from Northern Alberta,

1929-31.

Toronto: University of

Toronto Press, 1996.

Toronto: University of

Toronto Press, 1996.

Leonard, D.W. Delayed Frontier: the Peace River Country to 1909.

Calgary: Detselig Enterprises

Ltd., 1995.

Calgary: Detselig Enterprises

Ltd., 1995.

Simpson, C. A Yankee’s Adventures in South Africa.

Chicago: Thos. W. Jackson

Publishing Co., 1897.

Chicago: Thos. W. Jackson

Publishing Co., 1897.

Frank Jackson,

my Pa, married Mary Percy on March 10, 1931, in Battle River. But it wouldn’t

have happened if it hadn’t been for me. Pa was too shy to ask Mary himself,

but I could tell he sure liked her a lot. He was always bringing patients to

her, just so as he could visit. He even bribed Moostoos, our farm hand, into

letting Pa take him down to see Dr. Mary for an ingrown toe nail. Moostoos would

just as soon have chopped the toe off himself. Lots of fellows were keen on

Mary. She was always invited to one party or another. She sometimes stayed up

all night dancing. I remember the women talking at Keg River Sunday socials,

scandalized by Mary’s many gentlemen friends. I knew if Pa didn’t do something

quick, someone else would snap her up.

Frank Jackson,

my Pa, married Mary Percy on March 10, 1931, in Battle River. But it wouldn’t

have happened if it hadn’t been for me. Pa was too shy to ask Mary himself,

but I could tell he sure liked her a lot. He was always bringing patients to

her, just so as he could visit. He even bribed Moostoos, our farm hand, into

letting Pa take him down to see Dr. Mary for an ingrown toe nail. Moostoos would

just as soon have chopped the toe off himself. Lots of fellows were keen on

Mary. She was always invited to one party or another. She sometimes stayed up

all night dancing. I remember the women talking at Keg River Sunday socials,

scandalized by Mary’s many gentlemen friends. I knew if Pa didn’t do something

quick, someone else would snap her up.