Criminals or Critics? Reflections on Clayoquot

Abstract

Over 900 individuals were arrested for blockading the Kennedy

Lake logging road during the summer of 1993. Eight hundred sixty

of those were brought to trial (Hatch 1994). I was one of them.

This mass arrest and following cattle car justice was the result

of cumulative public discontent. The public are aware of the corporate

vandalism that has and remains to take place on their property.

My motivations for participating in this act of civil disobedience

grew out of my growing knowledge of the separateness of our economy

and our ecology. Labeling their decision the "Clayoquot Compromise",

the government standard ‘decide, announce and defend’ (D.A.D)

planning process was recognized and rejected by the public. Those

who recognized the obvious economic and ecological damage of doing

business as usual in Clayoquot were forced to leave the planning

process as the government allowed the trans-national logging companies,

MacMillan Bloedel and International Forest Products, to continue

logging operations while land use debates were under way. The government

did not recognize the public awareness of the situation and continued

the process without full interest participation. The result, the

largest act of civil disobedience in Canadian history. This event

denotes a shift in public sentiment regarding wasteful industrial

forestry practices from that of being a necessary evil to becoming

a criminal act that will no longer be tolerated (Pendleton 1995).

On November 23rd, 1993, I stood before Mr. Justice Hutchinson

of the Supreme Court of British Columbia and pleaded not guilty

to a charge of criminal contempt of court. I did however plead

guilty to attempts at preserving biodiversity, preventing clear-cut

logging in old growth temperate rain forest, addressing unsettled

aboriginal land claims and opposing the whole-sale rape of BC’s

ecological and economic capital. The outcome, I spent a week in

jail and twenty-one days under house arrest with an electronic

monitoring device strapped to my ankle. Almost five years latter,

I can now reflect on the occurrences of the summer of 1993 and

conclude that the arrest of myself and some 900 other individuals

was an important and necessary event displaying the publics desire

for increasing the intensity of public involvement with regards

to our natural resources.

The

Clayoquot Sound protesters, I believe, were the proverbial straw

that broke the camels back. An event that brought about massive

forest policy change and brought the public to the land use decision

tables. Most importantly, however, is the paradoxical situation

in which the private sector attempted to use the court system to

turn critics into criminals. When the dust settled however, the

real criminals in the eyes of the public, were those who perpetuated

and clung to the wasteful industrial logging practices that the

public now perceived as criminal (Pendleton 1995). The

Clayoquot Sound protesters, I believe, were the proverbial straw

that broke the camels back. An event that brought about massive

forest policy change and brought the public to the land use decision

tables. Most importantly, however, is the paradoxical situation

in which the private sector attempted to use the court system to

turn critics into criminals. When the dust settled however, the

real criminals in the eyes of the public, were those who perpetuated

and clung to the wasteful industrial logging practices that the

public now perceived as criminal (Pendleton 1995).

Clear-Cut or Selective Democracy

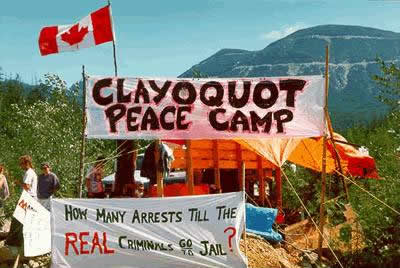

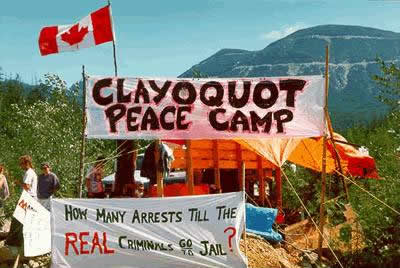

During the summer of 1993 a beautiful thing happened on a logging

road that entered the largest remaining intact temperate rain forest

on Vancouver Island. The Clayoquot Sound civil disobedience protest

saw over 900 individuals arrested (Hatch 1994). Why was this beautiful?

Simply because a diverse group of concerned citizens of not only

Canada, but the world, united and enforced clear-cut democracy

on those who prefer a more selective approach.

During August, 1989, the Province of British Columbia developed

the Clayoquot Sound Sustainable Development Task Force. It’s

task, to resolve land use disputes in Clayoquot Sound (Greer and

Kucey 1997). The process failed miserably because the "architects" of

the process, the BC Ministries of Environment and Regional and

Economic Development, failed to implement the "...fundamental

precepts of consensus based negotiation" and because the process "...failed

to effect the necessary transition from a competitive to a collaborative

negotiating orientation" (Darling 1991). It was these architectural

flaws that created an environment suitable for a selectively democratic

process favouring the corporate/government agenda of continuing

single use management, industrial logging.

It was recognized by the Friends of Clayoquot Sound, during the

Sulphur Pass conflict (summer of 1988), that BC’s new "Regionalization

Framework for Action" called for the reflection of community "...needs

and aspirations" and sustainability (Darling 1991). Out of

this grew the "...sustainable development strategy for Clayoquot

Sound Steering Committee" (Darling 1991). Six months latter

a twenty-seven page document was presented to the BC Environment

and Land Use Committee. It was rejected by both industry and government

and in its place, The Clayoquot Sound Sustainable Development Task

Force was announced. It was conceived by a private meeting between

the Minister of Environment and the Mayors of Port Alberni, Ucluelet

and Tofino. "Neither the Tofino Steering Committee, the Native

Bands of Clayoquot Sound, the friends of Clayoquot Sound, nor any

other stake holder was consulted or otherwise involved in the meeting" (Darling

1991). In essence, the public involvement process plummeted from

the possible total participation level of citizen control to that

of complete non-participation; manipulation and therapy (Arnstein

1969). Short term economic gain won out over democratic community

involvement. Government and industry opted for the practice of

selective democracy over clear-cut democracy.

After spending 12 days in court, a week in prison and 21 days

under house arrest, it became very clear to me that democracy is

not upheld or enforced by law. It is fought for continuously by

responsible individuals who recognize and accept their collective role

in the democratic society. The Clayoquot mass trials were largely "show

trials" (Hatch p.107). Their purpose, to "show" the

public the consequences of civil dissent. A truly democratic system

would have dealt with the fundamental issues rather than host a

kangaroo court. Insults to democratic society were witnessed daily

throughout the entire process. One of these was the refusal by

the courts to allow trial by jury. The court injunction applied

for and administered by MacMillan and Bloedel set the seen where

the criminal offense was not perpetuated against the destructive

logging practices of MacMillan Bloedel, but against the judiciary.

This created a circumstance where the offended party (who was not

even present

for the ‘offense’) was the judiciary. The flaw here is

that the offended party was the judge, the jury and the person

responsible for passing the sentence! Prominent Vancouver lawyer,

Richard Peck, pointed out that historically, contempt trials were

conducted by jury (Hatch p.111). There was also a continuous flip

flopping of the court as to whether the diverse group of Clayoquot

Protectors (aka Protesters) were individuals or a single entity.

When it pleased the courts to treat the defendants as a group,

they did. And vice versa. For example, as the mass trials progressed,

previous interpretations of ideas and events from individual defendants

were transposed onto the current defendants and the judge disallowed

the current defendant’s interpretation of events. The courts

painted a very diverse crowd of 860 people with the same brush.

By doing so the court once again ignored the democratic rights

of individuals. Perhaps the most flagrant example of the court

attacking democracy was Mr. Justice Bouk’s statement that

the judiciary is "... sort of allowed to make the rules as

(the trials) go along" (Hatch p.108). Law in our society is

based on precedent. A justice making up the rules on the fly undermines

all ideals of law in a democratic society (Hatch p.108). It is

not surprising that as I sat through this circus the lyrics of

a Billy Bragg song rang through my mind "...The judge said, ‘This

isn’t a court of justice son! This is a court of law!" present

for the ‘offense’) was the judiciary. The flaw here is

that the offended party was the judge, the jury and the person

responsible for passing the sentence! Prominent Vancouver lawyer,

Richard Peck, pointed out that historically, contempt trials were

conducted by jury (Hatch p.111). There was also a continuous flip

flopping of the court as to whether the diverse group of Clayoquot

Protectors (aka Protesters) were individuals or a single entity.

When it pleased the courts to treat the defendants as a group,

they did. And vice versa. For example, as the mass trials progressed,

previous interpretations of ideas and events from individual defendants

were transposed onto the current defendants and the judge disallowed

the current defendant’s interpretation of events. The courts

painted a very diverse crowd of 860 people with the same brush.

By doing so the court once again ignored the democratic rights

of individuals. Perhaps the most flagrant example of the court

attacking democracy was Mr. Justice Bouk’s statement that

the judiciary is "... sort of allowed to make the rules as

(the trials) go along" (Hatch p.108). Law in our society is

based on precedent. A justice making up the rules on the fly undermines

all ideals of law in a democratic society (Hatch p.108). It is

not surprising that as I sat through this circus the lyrics of

a Billy Bragg song rang through my mind "...The judge said, ‘This

isn’t a court of justice son! This is a court of law!"

The Clayoquot protest became the largest act of civil disobedience

in Canadian history. There has been no other circumstance in Canadian

history where over 800 people were arrested (and tried) for an

act of civil disobedience (Dearden p.236). According to United

Nations crime statistics (United Nations Web Page), Canadians are

an extremely law abiding society. The average Canadian pedestrian

at 4:00 AM would probably wait for the flashing ‘WALK’ sign

before venturing to cross a barren intersection. The extreme measures

resorted to by the public marked a turning point in government

and corporate methods of public involvement. The public wanted

their say and they wanted to be heard. This public action also

denotes a pivotal point in defining what indeed a criminal act

is in BC. Society decided that the current industrial logging practices

in BC were in fact criminal acts against not only nature, but public

property. The result, the Forest Practices Code and the "criminalization

of logging" (Pendleton 1995).

The private trans-national forestry companies, MacMillan Bloedel

and International Forest Products, used the law to protect their

private interest on public land. The law enabled them to continue

their destructive practices, but once the smoke settled, a shift

in public sentiment became apparent. The public now view those

who destroy ecosystems for short term profit from that of a corporate ‘white

collar’ crime to viewing these individuals and corporations

as common criminals.

World Views and Motivations

Which restaurant would you prefer: the ‘Block

and Cleaver’ or ‘The Common Loaf’? The answer,

may lie in your world view. If you happen to subscribe to the

expansionist paradigm, your choice may be Ucleulet’s ‘Block

and Cleaver’. If, on the other hand, you consider yourself

as having a "steady state" or ecological world view,

you may prefer Tofino’s ‘The Common Loaf’. The

reasoning behind this assumption is that Tofino was forced into

recognizing other values than those prescribed by the expansionist

paradigm due to a sudden decline in forestry jobs. The 1984 amalgamation

of Tree Farm License (TFL) 21, covering Clayoquot sound, and

TFL 22, covering the Alberni Valley, the Alberni Canal and Barkley

Sound, to form TFL 44 created a situation where, based on economics,

industry concentrated it’s cut in areas other than central

Clayoquot Sound. This strategy "...further entrenched the

industry as the major employer in Ucluelet and Port Alberni" (Darling

1991). A climate suitable for the development of an ecological

world view was created in Tofino as the community was forced

into recognizing other land use values than timber extraction.

Meanwhile, in neighbouring Uclelet, the expansionist paradigm

flourished. Passed and present forestry practices near Uclelet

created a situation not conducive to other resource values. For

example, the view of denuded land is not conducive to tourism. "Thus,

the industry’s harvest agenda, driven by corporate rather

than community objectives, inadvertently set the stage for conflict" (Darling

1991).

Some of the Mac Blow hired guns read the injunction.

The RCMP gave these individuals access

to private, sensitive records of all

arrested.

"Protection of the environment is a responsibility

shared by all levels of government as well as by industry , organized

labour and individuals." The latter quote is taken

directly from the Canadian Environmental Protection Act : Enforcement

and Compliance Policy (1993). It, along with many scientific

and economic facts are the easily defensible reasons behind my ‘criminal’ actions.

The major motivation however, the intrinsic value of our natural

world, was a difficult value to defend. The steady state or ecological

world view subscribes to the belief that the economy is "...inextricably

integrated, completely contained, and a wholly dependent subsystem

of the ecosphere" (Rees 1995). Such a philosophy, or as

I believe, fact, places many values on nature rather than merely

monetary worth. This concept can never be accepted among the

current corporate extractive industries. Such a union can only

result with the acknowledgment that our economic capital has

been irrevocably damaged and society as a whole will recognize

what it has lost to the voracious appetite of corporate extractive

industry. The expansionist ideal is that we take from the natural

resource loop, and convert the raw material into money for the

economic loop, assuming that both will grow endlessly. Like our

neo-classical economic system, our courts view the intrinsic

value of nature as an externality because quantifying it is currently

to difficult. The intrinsic values along with the collective

social interest; forests, fish (M’Gonigle and Parfitt 1994),

clean air and sustainablity were lost in the paper work as the

trials rolled on.

Criminals or Critics?

The very essence of individualism is

the refusal to mind your own business. This is not a

particularly pleasant or easy style of life. It is not

profitable, efficient, competitive or rewarded. It often

consists of being persistently annoying to others as

well as being stubborn and repetitive...

Criticism is perhaps the citizen's

primary weapon in the exercise of her legitimacy. That

is why, in this corporatist society, conformism, loyalty

and silence are so admired and rewarded; why criticism

is so punished or marginalized. Who has not experienced

this conflict?

John Ralston Saul

Some of the 'Criminals' fresh out of the holding pen in

Ucleulet. Twelve days of court, prison time

(one week for me), 21 days electronic monitoring and 250 community

hours to go...

From left: Joanne, myself, Ernest and Kevin.

Problems and conflicts have occurred throughout history and will

continue to occur. Solutions are always sought to solve these issues

and critics are always present to evaluate the proposed and imposed

solutions. The BC Provincial Government and MacMillan Bloedel imposed

their solution to the Clayoquot dispute with very little public

involvement. The effected communities, the provincial, national

and global public have made it clear that the solution to the dispute

could not work. These people became aware of the problem because

of the sacrifice of 860 Clayoquot critics.

John Ralston Saul eloquently describes the critic’s sacrifice

and the conformist material rewards. This is very applicable to

what took place at the Kennedy Lake Bridge in Clayoquot sound.

Thousands of citizens blockaded or supported blockades who were

displaying there criticism for their government’s corporate

logging policies. The corporations and the government quickly defended

there decisions by labeling these individuals as ‘criminals’ instead

of accepting them for what they truly were, critics.

This coalition between the BC Provincial Government and MacMillan & Bloedel

was completely understandable if one considers the following. On

February 8, 1993, the BC Provincial Government held 1.5% of MacMillan

Bloedel’s outstanding shares. On February 9, 1993 the BC Provincial

Government was made aware that the major shareholder in MacMillan

Bloedel was placing 49% of outstanding shares on the market. By

the end of the day, the governments stake in MacMillan Bloedel

had leaped from 1.5% of outstanding shares to that of 3.5%. The

Provincial government made its land use decision concerning Clayoquot

sound on April 13, 1993, after more than doubling its share holdings

in the corporation. Mr. Justice P.D. Seaton found that there was

no conflict of interest in this purchase. After reading his decision

which was spent largely defining ‘conflict of interest’,

and after being exposed to the system of justice we rely on. I

am very skeptical of the outcome.

The critics of the Clayoquot Sound land use decision were making

society aware of the fundamental transformation society, as a whole,

must make to become truly sustainable. This is a very discomforting

for many who have profited or become accustomed to the current

paradigm. We are being driven by "...institutional inertia" (M’Gonigle).

A few of the Clayoquot Sound critics worked in the forestry industry.

It was these individuals, intermingling with the rest of the critics

who represented "...an emerging social consensus... hidden

beneath anger and frustration. It offers us many ways to get there,

and ironically, it is articulated by the very people who seem on

the surface to be diametrically opposed to one another, the environmentalist

and the mill worker" (M’Gonigle 1994). There may be room

for optimism when more of the industry workers and environmentalists

recognize their common goal.

No Body Likes a Critic

I was a criminal, according to our penal system, from August 31,

1993 until August 31, 1994. I am no longer a criminal, in the eyes

of our penal system as I complied with Justice Hutchison’s

orders which restricted my ability to continue my criticism with

my physical presence at Clayoquot. I was, throughout the whole

ordeal, and remain to be, a critic.

Seventy-one

percent of the Canadian population were against the protests

and 66% of the population were in support of the injunction to

stop protesters. The most important statistics to be considered

however, are that 67% of the population now oppose clear-cut

logging, and 64% want more government scrutiny and enforcement

of environmental laws (Pendelton 1996). Nobody likes a critic,

but they are a necessary component to a functioning democratic

society. The Clayoquot sound protesters are not criminals in

the eyes of the public, rather critics. And they gave the government

and the corporate forestry sector 860 thumbs down. Seventy-one

percent of the Canadian population were against the protests

and 66% of the population were in support of the injunction to

stop protesters. The most important statistics to be considered

however, are that 67% of the population now oppose clear-cut

logging, and 64% want more government scrutiny and enforcement

of environmental laws (Pendelton 1996). Nobody likes a critic,

but they are a necessary component to a functioning democratic

society. The Clayoquot sound protesters are not criminals in

the eyes of the public, rather critics. And they gave the government

and the corporate forestry sector 860 thumbs down.

References

Arnstein, S.R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal

of the American Planning Association. 35: 4. p. 217

Environment Canada (1993). Enforcement and

Compliance Policy, Canadian Environmental Protection Act :

p. 14.

Darling, R.D. (1991). In Search of Consensus:

an evaluation of the Clayoquot Sound Sustainable Development

Task Force process. p. 4-12.

Greer, D. and Kucey, K. (1997). Deciding the fate of the rain

forest: conflict and compromise. In Seeing The Ocean Through

The Trees. Ecotrust Canada. p. 19-28.

Hatch, R.B. (1994). The Clayoquot Show Trials. In Clayoquot & Dissent.

Ronsdale Press. p. 105-149.

M’Gonigle, Michael, & Parfitt, Ben. (1994). Forestopia:

A practical guide to the new forest economy. Harbour Publishing,

Maderia Park, BC Canada. p. 14-15

Pendleton R. Michael (1997). Beyond the threshold: the criminalization

of logging. Society & Natural Resources, 10:

181-193.

Rees, William, E (1995). Achieving Sustainability: Reform or transformation? Journal

of Planning Literature, Vol. 9, (4): 343-361.

Saul, John, Ralston (1995). Speech given at the Vancouver Writers

Festival.

Seaton, P.D., The Honourable Mr. Justice. (1993). Report of

the Commission of Inquiry into the allegations of conflict of

interest (MacMillan Bloedel Ltd. share purchase and Clayoquot

Sound land use decision). Pursuant to the Inquiry Act, R.S.B.C.

1979, chapter 198, part 2.

|

The

Clayoquot Sound protesters, I believe, were the proverbial straw

that broke the camels back. An event that brought about massive

forest policy change and brought the public to the land use decision

tables. Most importantly, however, is the paradoxical situation

in which the private sector attempted to use the court system to

turn critics into criminals. When the dust settled however, the

real criminals in the eyes of the public, were those who perpetuated

and clung to the wasteful industrial logging practices that the

public now perceived as criminal (Pendleton 1995).

The

Clayoquot Sound protesters, I believe, were the proverbial straw

that broke the camels back. An event that brought about massive

forest policy change and brought the public to the land use decision

tables. Most importantly, however, is the paradoxical situation

in which the private sector attempted to use the court system to

turn critics into criminals. When the dust settled however, the

real criminals in the eyes of the public, were those who perpetuated

and clung to the wasteful industrial logging practices that the

public now perceived as criminal (Pendleton 1995). present

for the ‘offense’) was the judiciary. The flaw here is

that the offended party was the judge, the jury and the person

responsible for passing the sentence! Prominent Vancouver lawyer,

Richard Peck, pointed out that historically, contempt trials were

conducted by jury (Hatch p.111). There was also a continuous flip

flopping of the court as to whether the diverse group of Clayoquot

Protectors (aka Protesters) were individuals or a single entity.

When it pleased the courts to treat the defendants as a group,

they did. And vice versa. For example, as the mass trials progressed,

previous interpretations of ideas and events from individual defendants

were transposed onto the current defendants and the judge disallowed

the current defendant’s interpretation of events. The courts

painted a very diverse crowd of 860 people with the same brush.

By doing so the court once again ignored the democratic rights

of individuals. Perhaps the most flagrant example of the court

attacking democracy was Mr. Justice Bouk’s statement that

the judiciary is "... sort of allowed to make the rules as

(the trials) go along" (Hatch p.108). Law in our society is

based on precedent. A justice making up the rules on the fly undermines

all ideals of law in a democratic society (Hatch p.108). It is

not surprising that as I sat through this circus the lyrics of

a Billy Bragg song rang through my mind "...The judge said, ‘This

isn’t a court of justice son! This is a court of law!"

present

for the ‘offense’) was the judiciary. The flaw here is

that the offended party was the judge, the jury and the person

responsible for passing the sentence! Prominent Vancouver lawyer,

Richard Peck, pointed out that historically, contempt trials were

conducted by jury (Hatch p.111). There was also a continuous flip

flopping of the court as to whether the diverse group of Clayoquot

Protectors (aka Protesters) were individuals or a single entity.

When it pleased the courts to treat the defendants as a group,

they did. And vice versa. For example, as the mass trials progressed,

previous interpretations of ideas and events from individual defendants

were transposed onto the current defendants and the judge disallowed

the current defendant’s interpretation of events. The courts

painted a very diverse crowd of 860 people with the same brush.

By doing so the court once again ignored the democratic rights

of individuals. Perhaps the most flagrant example of the court

attacking democracy was Mr. Justice Bouk’s statement that

the judiciary is "... sort of allowed to make the rules as

(the trials) go along" (Hatch p.108). Law in our society is

based on precedent. A justice making up the rules on the fly undermines

all ideals of law in a democratic society (Hatch p.108). It is

not surprising that as I sat through this circus the lyrics of

a Billy Bragg song rang through my mind "...The judge said, ‘This

isn’t a court of justice son! This is a court of law!"

Seventy-one

percent of the Canadian population were against the protests

and 66% of the population were in support of the injunction to

stop protesters. The most important statistics to be considered

however, are that 67% of the population now oppose clear-cut

logging, and 64% want more government scrutiny and enforcement

of environmental laws (Pendelton 1996). Nobody likes a critic,

but they are a necessary component to a functioning democratic

society. The Clayoquot sound protesters are not criminals in

the eyes of the public, rather critics. And they gave the government

and the corporate forestry sector 860 thumbs down.

Seventy-one

percent of the Canadian population were against the protests

and 66% of the population were in support of the injunction to

stop protesters. The most important statistics to be considered

however, are that 67% of the population now oppose clear-cut

logging, and 64% want more government scrutiny and enforcement

of environmental laws (Pendelton 1996). Nobody likes a critic,

but they are a necessary component to a functioning democratic

society. The Clayoquot sound protesters are not criminals in

the eyes of the public, rather critics. And they gave the government

and the corporate forestry sector 860 thumbs down.